Our History

Learn Our History, Our Stories *Information from different resources

What To Watch

The Death and Life of Marsha P. Johnson

This documentary re-examines the death of legend Marsha P. Johnson who died in the Hudson River. Ruled as a suicide, many people believe she was murdered

LA 92

This depicts the verdict of the Rodney King trial in 1992, when four police officers beat a black motorist

Hale County This Morning, This Evening

Recounted personally by black lives from the south and how they were affected by their racism

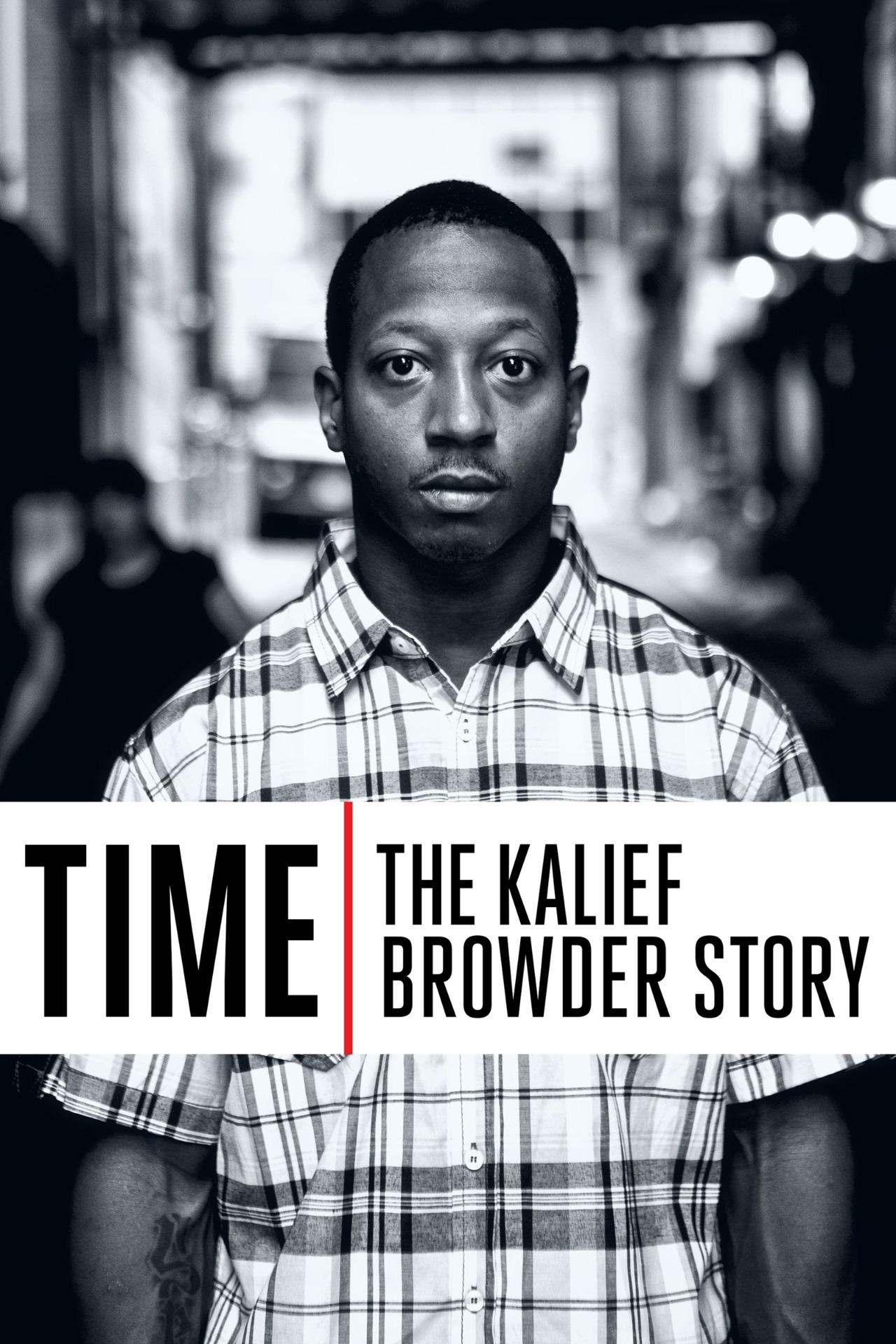

Time: The Kalief Browder Story

This six part documentary takes a tragic look into the young teen that spent three years in jail despite never committing a crime. This will make you second guess the justice system (if you haven't already)

The Black Panthers: Vanguard of the Revolution

Examines the rise of the Black Panthers and their impact they had on America and Civil Rights

The 13th

Focuses on the history of inequality in America, specifically the nation's prisons

Soundtrack for a Revolution

Examines the importance of music during the U.S. civil rights movement that took place during the 1950s and '60s

Who Killed Malcom X?

A 6 part documentary investigation the life and death of Malcom X.

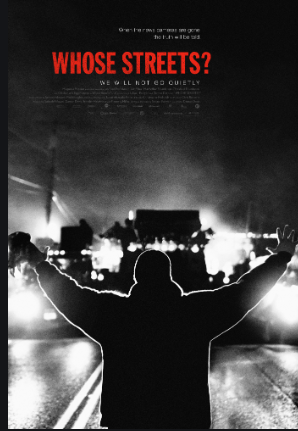

Whose Streets?

This documentary is about the Ferguson uprising back in 2014 and is recounted by the people who lived it

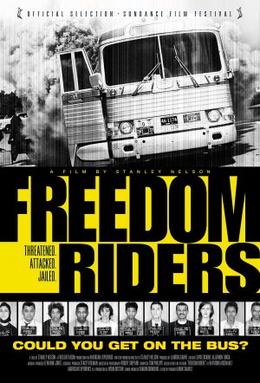

Freedom Riders

This talks about the Civil Rights activists' peaceful fights on buses and trains during the 1960s

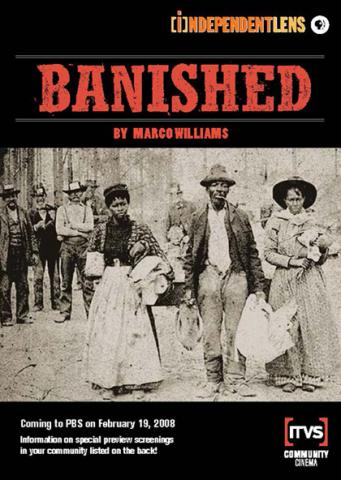

Banished

This documentary talks about four big cities in Texas, Missouri, Georgia and Indiana that violently forced African-American families to flee between the years 1886 and 1923

Hello, Privilege. It's Me, Chelsea

A documentary talking about white privilege from the point of view of a white women who's trying to understand it.

Slavery In America

Throughout the 17th and 18th centuries people were kidnapped from the continent of Africa, forced into slavery in the American colonies and exploited to work as indentured servants and labor in the production of crops such as tobacco and cotton. By the mid-19th century, America's westward expansion and the abolition movement provoked a great debate over slavery that would tear the nation apart in the bloody Civil War. Though the Union victory freed the nation's four million enslaved people, the legacy of slavery continued to influence American history

When Did It Start

Many consider a significant starting point to slavery in America to be 1619, when the privateer The White Lion brought 20 African slaves ashore in the British colony of Jamestown, Virginia. The crew had seized the Africans from the Portuguese slave ship Sao Jao Bautista.

Throughout the 17th century, European settlers in North America turned to African slaves as a cheaper, more plentiful labor source than indentured servants, who were mostly poor Europeans. Though it is impossible to give accurate figures, some historians have estimated that 6 to 7 million enslaved people were imported to the New World during the 18th century alone, depriving the African continent of some of its healthiest and ablest men and women.

In the 17th and 18th centuries, enslaved Africans worked mainly on the tobacco, rice and indigo plantations of the southern coast, from the Chesapeake Bay colonies of Maryland and Virginia south to Georgia. After the American Revolution, many colonists-particularly in the North, where slavery was relatively unimportant to the agricultural economy-began to link the oppression of enslaved Africans to their own oppression by the British, and to call for slavery's abolition.

History Of Slavery

Enslaved people in the antebellum South constituted about one-third of the southern population. Most lived on large plantations or small farms; many masters owned fewer than 50 enslaved people. Slave owners sought to make their enslaved completely dependent on them through a system of restrictive codes. They were usually prohibited from learning to read and write, and their behavior and movement was restricted.

Many masters took sexual liberties with enslaved women, and rewarded obedient behavior with favors, while rebellious enslaved people were brutally punished. A strict hierarchy among the enslaved (from privileged house workers and skilled artisans down to lowly field hands) helped keep them divided and less likely to organize against their masters. Marriages between enslaved men and women had no legal basis, but many did marry and raise large families; most slave owners encouraged this practice, but nonetheless did not usually hesitate to divide families by sale or removal.

Slave Rebellions

Slave rebellions did occur within the system-notably ones led by Gabriel Prosser in Richmond in 1800 and by Denmark Vesey in Charleston in 1822-but few were successful. The revolt that most terrified white slaveholders was that led by Nat Turner in Southampton County, Virginia, in August 1831. Turner's group, which eventually numbered around 75 black men, murdered some 60 white people in two days before armed resistance from local white people and the arrival of state militia forces overwhelmed them.

Supporters of slavery pointed to Turner's rebellion as evidence that black people were inherently inferior barbarians requiring an institution such as slavery to discipline them, and fears of similar insurrections led many southern states to further strengthen their slave codes in order to limit the education, movement and assembly of enslaved people.

When Did Slavery End?

On September 22, 1862, Lincoln issued a preliminary emancipation proclamation, and on January 1, 1863, he made it official that "slaves within any State, or designated part of a State...in rebellion,...shall be then, thenceforward, and forever free." By freeing some 3 million enslaved people in the rebel states, the Emancipation Proclamation deprived the Confederacy of the bulk of its labor forces and put international public opinion strongly on the Union side. Though the Emancipation Proclamation didn't officially end all slavery in America-that would happen with the passage of the 13th Amendment after the Civil War's end in 1865-some 186,000 black soldiers would join the Union Army, and about 38,000 lost their lives.

Juneteenth

On June 19, 1865, about two months after the Confederate Gen. Robert E. Lee surrendered at Appomattox, Va., Union Gen. Gordon Granger arrived in Galveston, Texas, to inform enslaved African-Americans of their freedom and that the Civil War had ended. General Granger's announcement put into effect the Emancipation Proclamation, which had been issued more than two and a half years earlier on Jan. 1, 1863, by President Abraham Lincoln.

The holiday received its name by combining June and 19. The day is also sometimes called "Juneteenth Independence Day," "Freedom Day" or "Emancipation Day."

The History Of Black Wall Street

Greenwood, Tulsa, also known as "Black Wall Street", was one of the most commercially successful and affluent majority African-American communities in the United States.

Developing Black Wall Street

Founded in 1906, Greenwood was developed on Indian Territory, the vast area where Native American tribes had been forced to relocate, which encompasses much of modern-day Eastern Oklahoma. Some African Americans who had been former slaves of the tribes, and subsequently integrated into tribal communities, acquired allotted land in Greenwood through the Dawes Act, a U.S. law that gave land to individual Native Americans. And many black sharecroppers fleeing racial oppression relocated to the region as well, in search of a better life post-Civil War.

"Oklahoma begins to be promoted as a safe haven for African Americans who start to come particularly post emancipation to Indian Territory," The largest number of black townships after the Civil War were located in Oklahoma. Between 1865 and 1920, African Americans founded more than 50 black townships in the state.

O.W. Gurley, a wealthy black landowner, purchased 40 acres of land in Tulsa, naming it Greenwood after the town in Mississippi.

Built 'For Black People, by Black People'

"Gurley is credited with having the first black business in Greenwood in 1906," says Hannibal Johnson, author of Black Wall Street: From Riot to Renaissance in Tulsa's Historic Greenwood District. "He had a vision to create something for black people by black people."

Gurley started with a boarding house for African Americans. Then word began to spread about opportunities for blacks in Greenwood and they flocked to the district. "O.W. Gurley would actually loan money to people who wanted to start a business," says Kristi Williams, vice chair of the African American Affairs Commission in Tulsa. "They actually had a system where someone who wanted to own a business could get help in doing that."

Other prominent black entrepreneurs followed suit. J.B. Stradford, born into slavery in Kentucky, later becoming a lawyer and activist, moved to Greenwood in 1898. He built a 55-room luxury hotel bearing his name, the largest black-owned hotel in the country. An outspoken businessman, Stradford believed that blacks had a better chance of economic progress if they pooled their resources.

Greenwood Became Self-Contained and Reliant

A.J. Smitherman, a publisher whose family moved to Indian Territory in the 1890s, founded the Tulsa Star, a black newspaper headquartered in Greenwood that became instrumental in establishing the district's socially-conscious mindset. The newspaper regularly informed African Americans about their legal rights and any court rulings or legislation that were beneficial or harmful to their community.

Demands for equal rights were an ongoing mission for blacks in Tulsa despite Jim Crow oppression. Greenwood itself had a railway track running through it that separated the black and white populations. Consequently, Gurley and Stradford's vision of having a self-contained and self-reliant black economy came to be not only by desire but by logistics.

"As a practical matter they had no choice as to where to locate their businesses," said Johnson. "Tulsa was rigidly segregated, and Oklahoma became increasingly racist after statehood." On Greenwood Avenue, there were luxury shops, restaurants, grocery stores, hotels, jewelry and clothing stories, movie theaters, barbershops and salons, a library, pool halls, nightclubs and offices for doctors, lawyers and dentists. Greenwood also had its own school system, post office, a savings and loan bank, hospital, and bus and taxi service.

Greenwood was home to far less affluent African Americans as well. A significant number still worked in menial jobs, such as janitors, dishwashers, porters, and domestics. The money they earned outside of Greenwood was spent within the district. "It is said within Greenwood every dollar would change hands 19 times before it left the community," said Place.

Time of Racial Violence

It wasn't long before the affluent African Americans attracted the attention of local white residents, who resented the upscale lifestyle of people they deemed to be an inferior race. "I think the word jealousy is certainly appropriate during this time," says Place. "If you have particularly poor whites who are looking at this prosperous community who have large homes, fine furniture, crystals, china, linens, etc., the reaction is 'they don't deserve that.'" With the resurgence of the Ku Klux Klan, blacks in Greenwood feared racial violence and the removal of their voting rights. The Oklahoma Supreme Court for years routinely upheld the state's restrictions on voting access for African Americans, subjecting them to the poll tax and literacy tests. And lynchings proliferated across the country, particularly during the Red Summer of 1919, where anti-black riots erupted in major cities across the United States, including Tulsa. In response, The Tulsa Star encouraged blacks to take up arms and to show up at courthouses and jails to make sure blacks who were on trial were not taken and killed by white lynch mobs.

The Devastation of Black Wall Street

During the Tulsa Race Massacre (also known as the Tulsa Race Riot), which occurred over 18 hours on May 31-June 1, 1921, a white mob attacked residents, homes and businesses in the predominantly black Greenwood neighborhood of Tulsa, Oklahoma. The event remains one of the worst incidents of racial violence in U.S. history, and one of the least-known: News reports were largely squelched, despite the fact that hundreds of people were killed and thousands left homeless.

What Caused the Tulsa Race Massacre?

On May 30, 1921, a young black teenager named Dick Rowland entered an elevator at the Drexel Building, an office building on South Main Street. At some point after that, the young white elevator operator, Sarah Page, screamed; Rowland fled the scene. The police were called, and the next morning they arrested Rowland. By that time, rumors of what supposedly happened on that elevator had circulated through the city's white community. A front-page story in the Tulsa Tribune that afternoon reported that police had arrested Rowland for sexually assaulting Page.

As evening fell, an angry white mob was gathering outside the courthouse, demanding the sheriff hand over Rowland. Sheriff Willard McCullough refused, and his men barricaded the top floor to protect the black teenager. Around 9 p.m., a group of about 25 armed black men-including many World War I veterans-went to the courthouse to offer help guarding Rowland. After the sheriff turned them away, some of the white mob tried unsuccessfully to break into the National Guard armory nearby. With rumors still flying of a possible lynching, a group of around 75 armed black men returned to the courthouse shortly after 10 pm, where they were met by some 1,500 white men, some of whom also carried weapons.

Greenwood Burns

After shots were fired and chaos broke out, the outnumbered group of black men retreated to Greenwood. Over the next several hours, groups of white Tulsans-some of whom were deputized and given weapons by city officials-committed numerous acts of violence against black people, including shooting an unarmed man in a movie theater. The false belief that a large-scale insurrection among black Tulsans was underway, including reinforcements from nearby towns and cities with large African-American populations, fueled the growing hysteria.

As dawn broke on June 1, thousands of white citizens poured into the Greenwood District, looting and burning homes and businesses over an area of 35 city blocks. Firefighters who arrived to help put out fires later testified that rioters had threatened them with guns and forced them to leave. According to a later Red Cross estimate, some 1,256 houses were burned; 215 others were looted but not torched. Two newspapers, a school, a library, a hospital, churches, hotels, stores and many other black-owned businesses were among the buildings destroyed or damaged by fire. By the time the National Guard arrived and Governor J. B. A. Robertson had declared martial law shortly before noon, the riot had effectively ended. Though guardsmen helped put out fires, they also imprisoned many black Tulsans, and by June 2 some 6,000 people were under armed guard at the local fairgrounds.

Aftermath of the Tulsa Race Massacre

In the hours after the Tulsa Race Massacre, all charges against Dick Rowland were dropped. The police concluded that Rowland had most likely stumbled into Page, or stepped on her foot. Kept safely under guard in the jail during the riot, he left Tulsa the next morning and reportedly never returned. The "official" tally of deaths in the massacre was 36 people killed, including 10 white people. Even by that estimate-which historians now consider much too low-the Tulsa Race Massacre stood as one of the deadliest riots in U.S. history, behind only the New York Draft Riots of 1863, which killed at least 119 people. In the years to come, as black Tulsans worked to rebuild their ruined homes and businesses, segregation in the city only increased, and Oklahoma's newly established branch of the KKK grew in strength.

News Blackout

For decades, there were no public ceremonies, memorials for the dead or any efforts to commemorate the events of May 31-June 1, 1921. Instead, there was a deliberate effort to cover them up. The Tulsa Tribune removed the front-page story of May 31 that sparked the chaos from its bound volumes, and scholars later discovered that police and state militia archives about the riot were missing as well. As a result, until recently the Tulsa Race Massacre was rarely mentioned in history books, taught in schools or even talked about. Scholars began to delve deeper into the story of the riot in the 1970s, after its 50th anniversary had passed. In 1996, on the riot's 75th anniversary, a service was held at the Mount Zion Baptist Church, which rioters had burned to the ground, and a memorial was placed in front of Greenwood Cultural Center.

Tulsa Race Riot Commission Established, Renamed

The following year, after an official state government commission was created to investigate the Tulsa Race Riot, scientists and historians began looking into long-ago stories, including numerous victims buried in unmarked graves. In 2001, the report of the Race Riot Commission concluded that between 100 and 300 people were killed and more than 8,000 people made homeless over those 18 hours in 1921. A bill in the Oklahoma State Senate requiring that all Oklahoma high schools teach the Tulsa Race Riot failed to pass in 2012, with its opponents claiming schools were already teaching their students about the riot.

According to the State Department of Education, it has required the topic in Oklahoma history classes since 2000 and U.S. history classes since 2004, and the incident has been included in Oklahoma history books since 2009. In November 2018, the 1921 Race Riot Commission was officially renamed the 1921 Race Massacre Commission. "Although the dialogue about the reasons and effects of the terms riot vs. massacre are very important and encouraged," said Oklahoma State Senator Kevin Matthews, "the feelings and interpretation of those who experienced this devastation as well as current area residents and historical scholars have led us to more appropriately change the name to the 1921 Race Massacre Commission."

The Black Panther Party

The Black Panthers, also known as the Black Panther Party, was a political organization founded in 1966 by Huey Newton and Bobby Seale to challenge police brutality against the African American community. Dressed in black berets and black leather jackets, the Black Panthers organized armed citizen patrols of Oakland and other U.S. cities. At its peak in 1968, the Black Panther Party had roughly 2,000 members. The organization later declined as a result of internal tensions, deadly shootouts and FBI counterintelligence activities aimed at weakening the organization.

Black Panthers History

Black Panther Party founders Huey Newton and Bobby Seale met in 1961 while students at Merritt College in Oakland, California. They both protested the college's "Pioneer Day" celebration, which honored the pioneers who came to California in the 1800s, but omitted the role of African Americans in settling the American West. Seale and Newton formed the Negro History Fact Group, which called on the school to offer classes in black history.

They founded the Black Panthers in the wake of the assassination of black nationalist Malcolm X and after police in San Francisco shot and killed an unarmed black teen named Matthew Johnson. Originally dubbed the Black Panther Party for Self-Defense, the organization was founded in October 1966. The Black Panthers' early activities primarily involved monitoring police activities in black communities in Oakland and other cities.

As they instituted a number of social programs and engaged in political activities, their popularity grew. The Black Panthers drew widespread support from urban centers with large minority communities, including Los Angeles, Chicago, New York and Philadelphia. By 1968, the Black Panthers had roughly 2,000 members across the country.

Political Activities And Social Programs

Newton and Seale drew on Marxist ideology for the party platform. They outlined the organization's philosophical views and political objectives in a Ten-Point Program. The Ten-Point Program called for an immediate end to police brutality; employment for African Americans; and land, housing and justice for all. The Black Panthers were part of the larger Black Power movement, which emphasized black pride, community control and unification for civil rights.

While the Black Panthers were often portrayed as a gang, their leadership saw the organization as a political party whose goal was getting more African Americans elected to political office. They were unsuccessful on this front. By the early 1970s, FBI counterintelligence efforts, criminal activities and an internal rift between group members weakened the party as a political force. The Black Panthers did, however, start a number of popular community social programs, including free breakfast programs for school children and free health clinics in 13 African American communities across the United States.

Black Panthers Violence And Controversies

The Black Panthers were involved in numerous violent encounters with police. In 1967, founder Huey Newton allegedly killed Oakland police officer John Frey. Newton was convicted of voluntary manslaughter in 1968 and was sentenced to two to 15 years in prison. An appellate court decision later reversed the conviction. Eldridge Cleaver, editor of the Black Panther's newspaper, and 17-year old Black Panther member and treasurer Bobby Hutton, were involved in a shootout with police in 1968 that left Hutton dead and two police officers wounded.

Conflicts within the party often turned violent too. In 1969, Black Panther Party member Alex Rackley was tortured and murdered by other Black Panthers who thought him a police informant. Black Panther bookkeeper Betty Van Patter was found beaten and murdered in 1974. No one was charged with the death, though many believed that party leadership was responsible.

The FBI And COINTELPRO

The Black Panthers' socialist message and black nationalist focus made them the target of a secret FBI counterintelligence program called COINTELPRO. In 1969, the FBI declared the Black Panthers a communist organization and an enemy of the United States government. The first FBI's first director, J. Edgar Hoover, in 1968 called the Black Panthers, "One of the greatest threats to the nation's internal security."

The FBI worked to weaken the Panthers by exploited existing rivalries between black nationalist groups. They also worked to undermine and dismantle the Free Breakfast for Children Program and other community social programs instituted by the Black Panthers. In 1969, Chicago police gunned down and killed Black Panther Party members Fred Hampton and Mark Clark, who were asleep in their apartment.

About a hundred bullets were fired in what police described as a fierce gun battle with members of the Black Panther Party. However, ballistics experts later determined that only one of those bullets came from the Panthers' side. Although the FBI was not responsible for leading the raid, a federal grand jury later indicated that the bureau played a significant role in the events leading up to the raid. The Black Panther Party officially dissolved in 1982.

New Black Panther Party

The New Black Panther Party is a black nationalist organization founded in Dallas, Texas, in 1989. Members of the original Black Panther Party say there's no relation between the New Black Panther Party and the original Black Panthers. The United States Commission on Civil Rights and the Southern Poverty Law Center have called the New Black Panther Party a hate group. In 2020 amongst the black lives matter movement there has been sighting of another Black Panther Party but has suspected members to be hired actors, but other than that there has been unnamed/unofficial groups of people dressed in black taking advantage of there 2nd amendment right like protester of the stay at home rules did spotted at protest also.

Members Of Black History

Click Any Of Their Images To Learn More

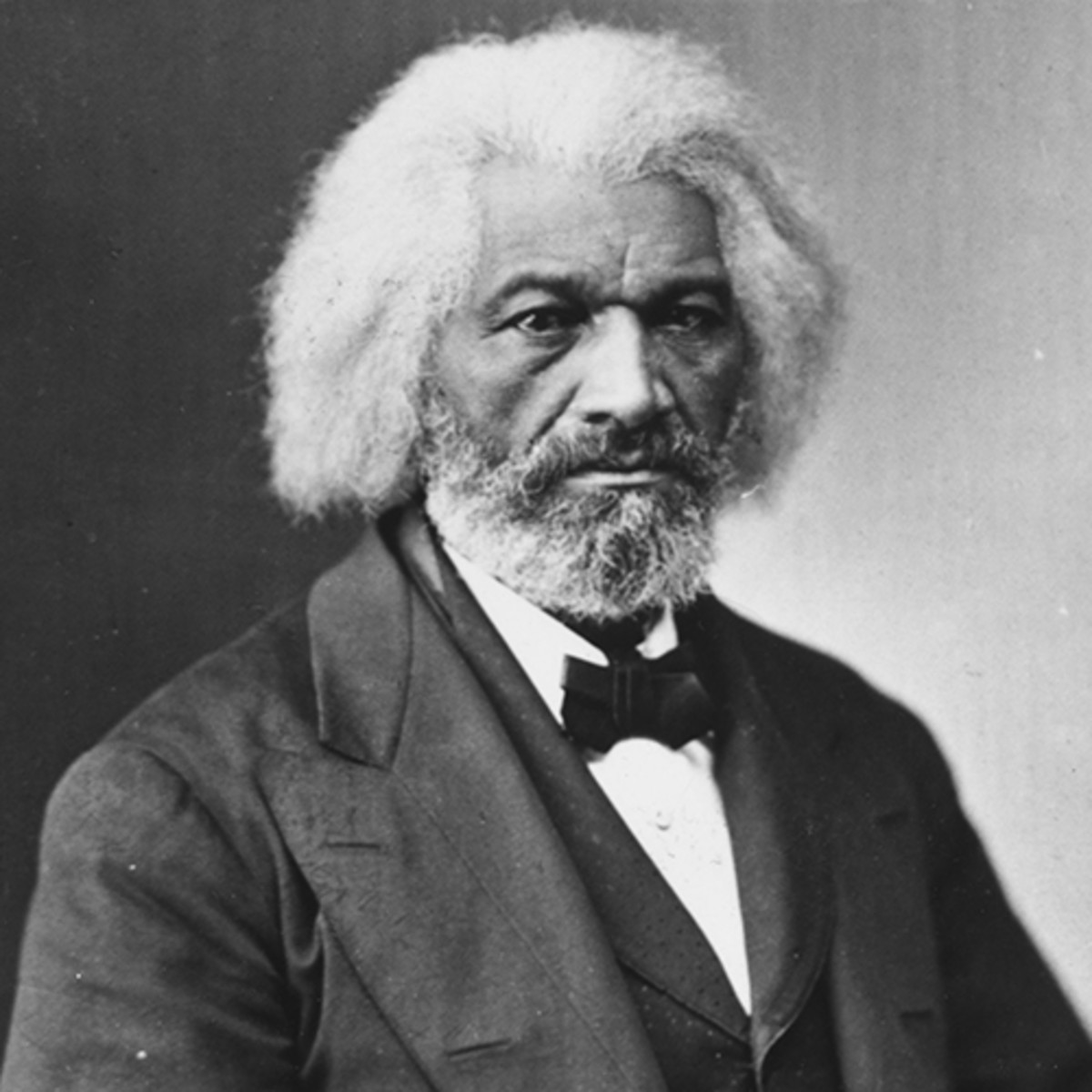

Frederick Douglass

an American social reformer, abolitionist, orator, writer, and statesman. After escaping from slavery, he became a national leader of the abolitionist movement in Massachusetts and New York.

Sojourner Truth

an American abolitionist and women's rights activist. Truth was born into slavery in Swartekill, New York, but escaped with her infant daughter to freedom in 1826. After going to court to recover her son in 1828, she became the first black woman to win such a case against a white man.

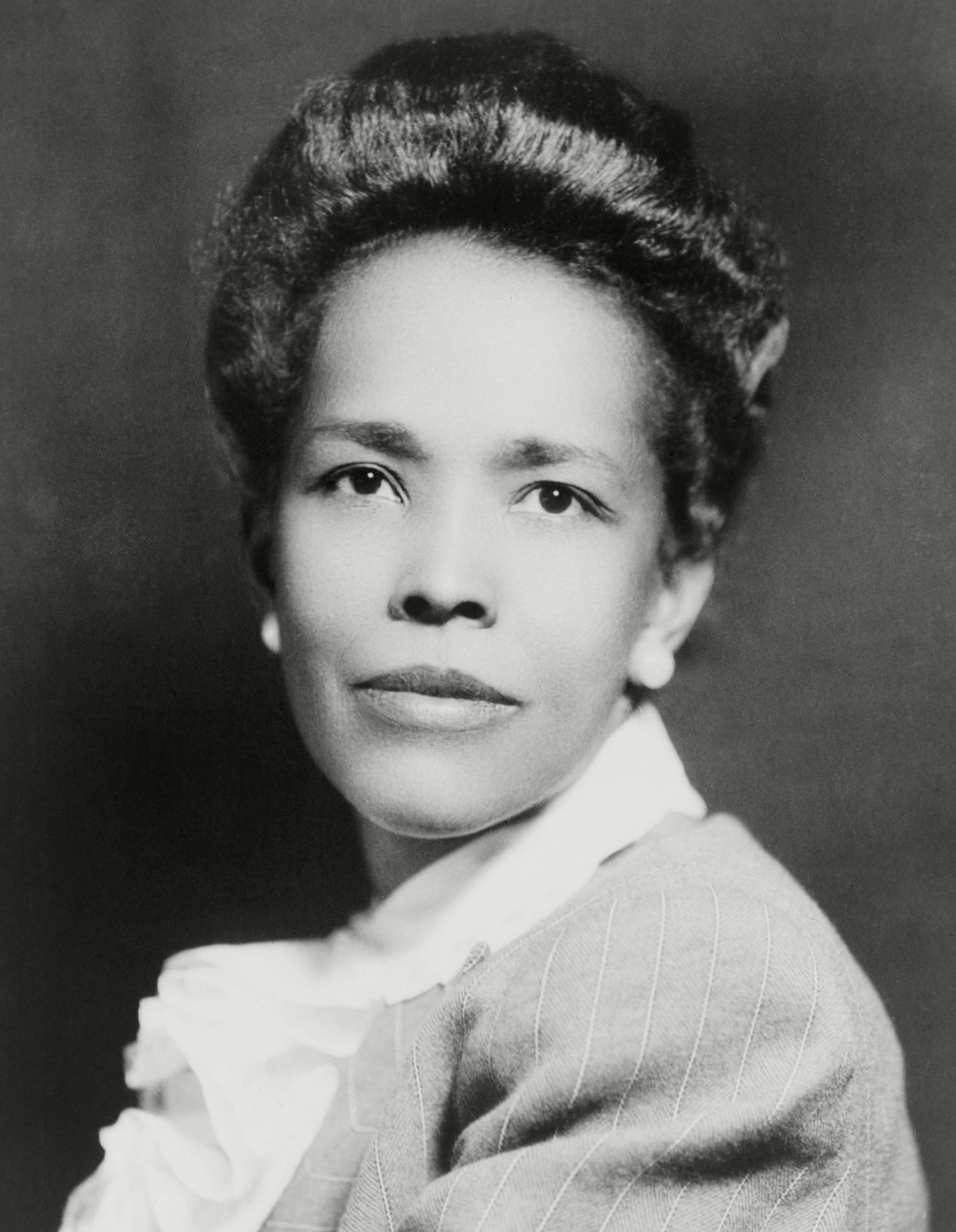

Ella Josephine Baker

an African-American civil rights and human rights activist. She was a largely behind-the-scenes organizer whose career spanned more than five decades. In New York City and the South, she worked alongside some of the most noted civil rights leaders of the 20th century

Ruby Bridges

American civil rights activist. She was the first African-American child to desegregate the all-white William Frantz Elementary School in Louisiana during the New Orleans school desegregation crisis on 14 November 1960.

Madam C. J. Walker

"the first black woman millionaire in America" and made her fortune thanks to her homemade line of hair care products for black women.

Angela Davis

an American political activist, philosopher, academic, and author.

Mary Jane McLeod Bethune

an American educator, stateswoman, philanthropist, humanitarian, womanist, and civil rights activist.

Rosa Parks

an American activist in the civil rights movement best known for her pivotal role in the Montgomery bus boycott. The United States Congress has called her "the first lady of civil rights" and "the mother of the freedom movement".

Myrlie Evers-Williams

an American civil rights activist and journalist who worked for over three decades to seek justice for the 1963 murder of her husband Medgar Evers, another civil rights activist.

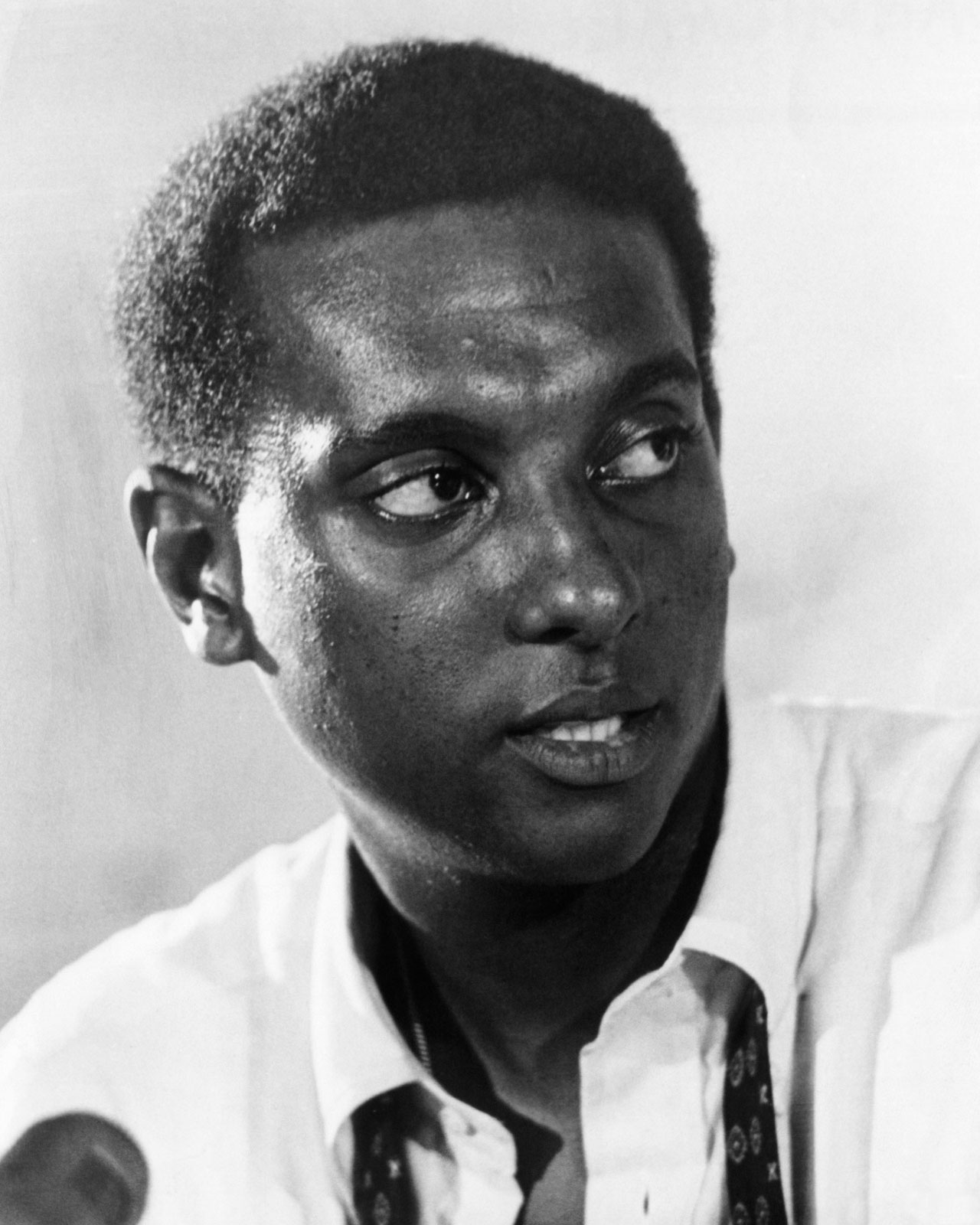

Stokely Carmichael

Kwame Ture (stokely) was a prominent Trinidadian organizer in the civil rights movement in the United States and the global Pan-African movement. Born in Trinidad, he grew up in the United States from the age of 11 and became an activist while attending Howard University.

Shirley Chisholm

an American politician, educator, and author. In 1968, she became the first black woman elected to the United States Congress, and she represented New York's 12th congressional district for seven terms from 1969 to 1983

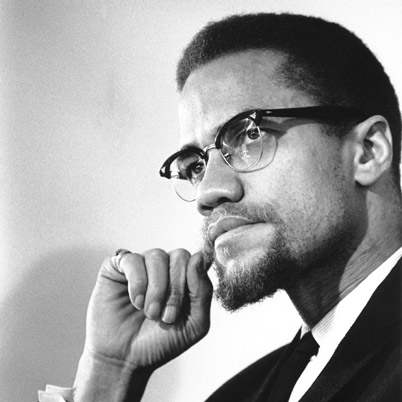

Malcolm X

an American Muslim minister and human rights activist who was a popular figure during the civil rights movement. He is best known for his staunch and controversial black racial advocacy, and for his time spent as the vocal spokesperson of the Nation of Islam.

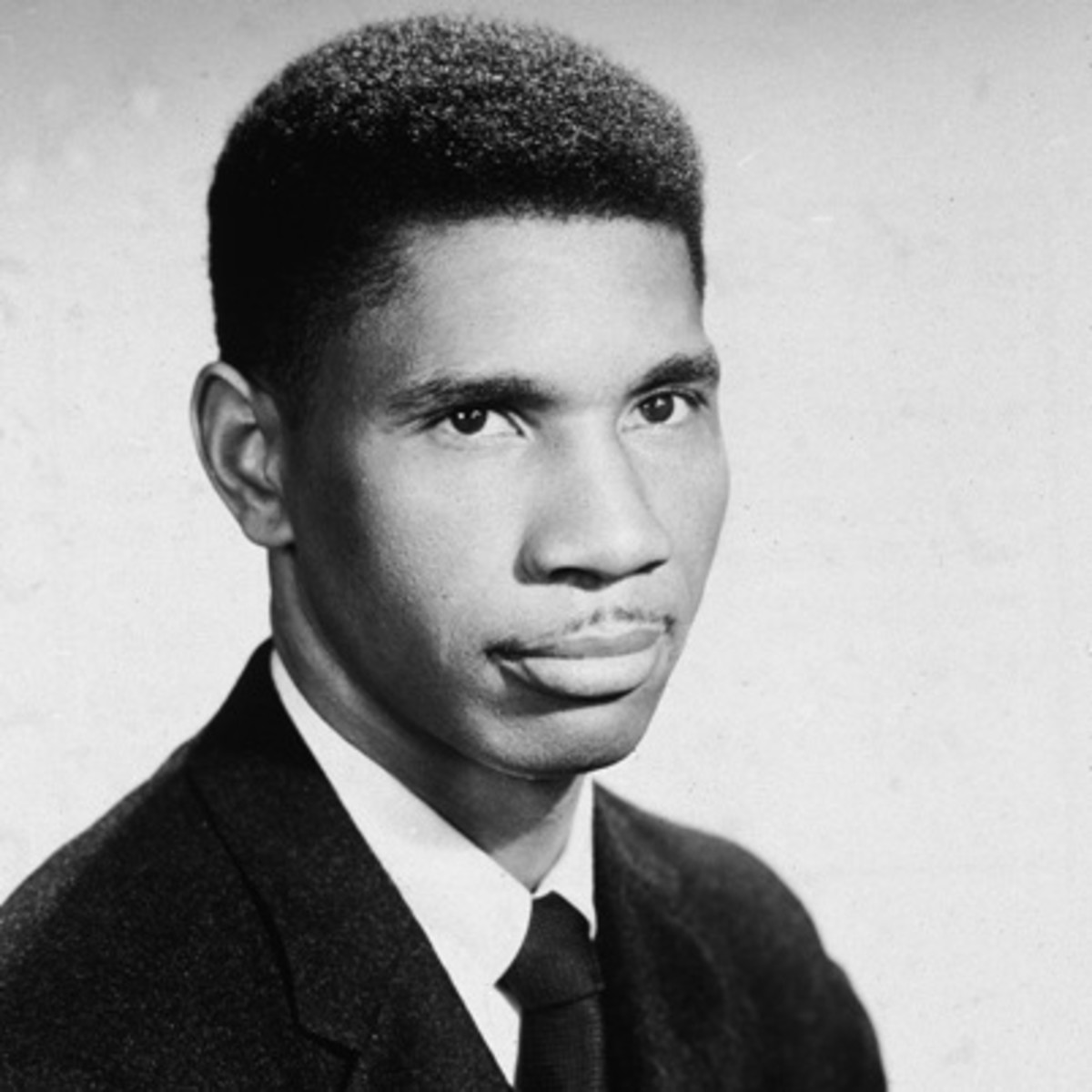

Medgar Wiley Evers

an American civil rights activist in Mississippi, the state's field secretary for the NAACP, and a World War II veteran who had served in the United States Army.

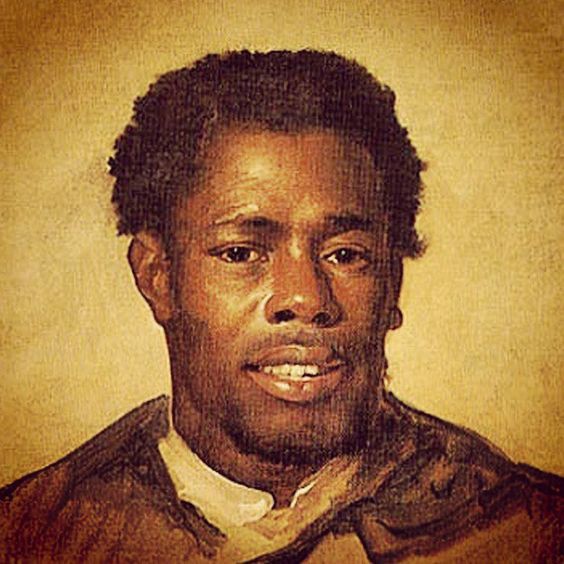

Nat Turner

An black American slave who led the only effective, sustained slave rebellion (August 1831) in U.S. history.

Harriet Tubman

an American abolitionist and political activist. Born into slavery, Tubman escaped and subsequently made some 13 missions to rescue approximately 70 enslaved people, including family and friends, using the network of antislavery activists and safe houses known as the Underground Railroad.

Martin Luther King Jr.

an American Christian minister and activist who became the most visible spokesperson and leader in the civil rights movement from 1955 until his assassination in 1968.